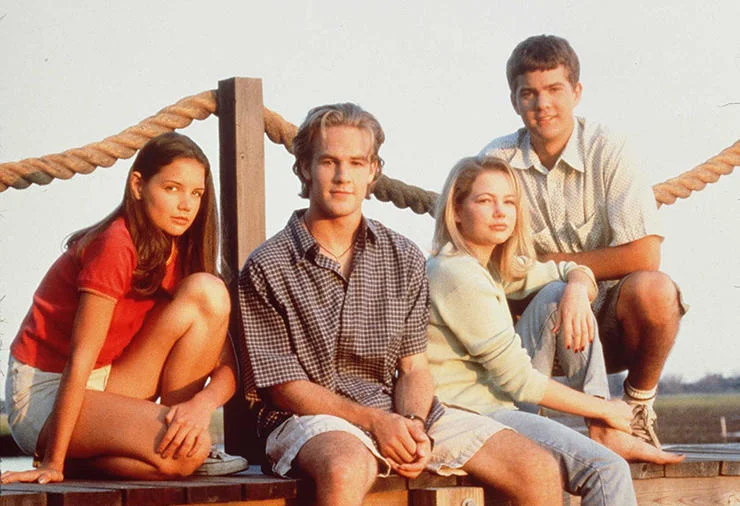

The Dawson's Creek Episode Guide: Detention

For a teen show, what’s a better trope than Saturday detention, a thing that doesn’t actually exist in the real world?

Read More

For a teen show, what’s a better trope than Saturday detention, a thing that doesn’t actually exist in the real world?

Read More

It only took six hours of programming, but I finally figured out why the Pacey/Tamara story has bothered me so much on this rewatch of Dawson’s Creek:

Read More

I’ve been cheated on before, and it’s one of the worst things that ever happened to me. I experienced a truly brutal mix of emotions: Plenty of rage and a healthy sense of betrayal, sure, but also a strong dose of failure and a powerful jolt of inadequacy. Our relationship was already fissured by the time this revelation came to light, so there was no hope for reconciliation. I reacted with a level of cruelty that I still find jarring, though on certain days I don’t think I was nearly harsh enough.

So while my initial reaction to Mitch Leery’s discovery that his wife Gail has been having an affair with her co-anchor was, “Man, this guy is on some serial killer shit,”

Read More

At the tail end of the fourth episode of Dawson's Creek's first season, Dawson says to his friend, "I'm mad at the world, Joey. I'm a teenager." I nearly went blind rolling my eyes into the back of my skull—not because that's a ridiculous line of dialogue (though it sort of is), but because I intoned that sentiment repeatedly during my puberty years.

Read More

Despite my commitment to Dawson's Creek, it turns out I'm a complete idiot. I have seen "Kiss," the third episode of Creek's premiere season, plenty of times, and only on this viewing did I notice that the fake name Joey uses with strange new gentleman Anderson Crawford is a variation on the name of the star of From Here to Eternity, which Dawson and Joey watch to kick off the episode.

Read More

Dawson Leery wants to be a filmmaker. His drive to pursue his dream is at the center of a lot of his decisions over the course of six seasons, and though the show sometimes forgets about Dawson's grand ambitions, it always manages to circle back to the idea that his dearest dream is to make movies (and in fact the very last scene of the finale is a revelation about his career). The pilot presented Dawson as a celluloid obsessive, what with his urge to get into the one film class at his high school, his carefully curated Spielberg obsession, and his yen to get himself into a junior film festival in Boston with a horror movie whose shoot is interrupted by the arrival of Jen.

So we know that the hunger is there, and that Dawson has acquired plenty of study in his obsessive re-watching of E.T., but what about his actual skills as a storyteller?

Read More

In the midst of all the celebration about the return of Mystery Science Theater 3000, I posited that no other piece of pop culture has been more responsible for my personality than that show.

Read MoreBack when I was an aspiring music theater performer, I took voice lessons once a week at the University of Hartford's Hartt School of Music. I started before I had a driver's license, but once I got access to a car that weekly trip became one the perpetual highlights of my week. I liked voice lessons enough, though the real thrill for me was the drive itself. The trip to Hartt was close enough to be convenient but just far enough away to really tuck into an album (generally, it was about a half hour of car time). The route also afforded me a handful of fast food outlets where I could treat myself, strange enough traffic patterns that would allow me plausible deniability should I disappear for longer than usual, and one glorious record store.

I'm pretty sure the shop was an outpost of a local chain called Record Express (there was another one within walking distance of my summer job at a bank in downtown Hartford), though it's possible it was just a Musicland or a Sam Goody. Either way, it was a very fine compact disc emporium with an exceptionally large retail footprint tucked between a Boston Market and a liquor store. I spent an insane amount of time and money in that place, and thinking back I'm amazed at its selection. That was the store where I found a lot of indie rock releases and a handful of new albums by forgotten bands (I distinctly remember the thrill of finding Crash Test Dummies' 1999 magnum opus Give Yourself a Hand, which I could not find anywhere else because nobody cared about Crash Test Dummies), but they also stocked a ton of hip-hop, and that is the place where I got a lot of my rap music education. A lot of the new rap was sold at a deeper discount than anything else, so I felt free to take flyers on a handful of big-selling but radio-unfriendly MCs.

In 1999, that meant brushing up against Master P's No Limit roster, and on the ride home from a voice lesson one night I traded a couple of bucks in my wallet for a copy of Silkk the Shocker's chart-topping album Made Man. Silkk had what I assume was an accidentally inventive flow, full of staccato hiccups and illogical shifts in speed and cadence. But he was a commercial force because he was Master P-adjacent (in fact, Silkk is P's younger brother), and Made Man debuted at the top of the Billboard 200 despite not having a big crossover single to break it in. I thought about 75 percent of Made Man was junk, though I did start to develop an appreciation for the minimalist bombast No Limit's Beats by the Pound production crew, and "It Takes More" is a great example of that: gangster movie strings, Miami bass thump, rickety snares, and a paranoid piano loop. It's a spartan masterpiece that I found unrefined in '99 but now wish was still the in sound of the moment.

That Dog's Retreat From the Sun turned 20 years old on Saturday, and they celebrated with a front-to-back performance of the album with a concert at the El Rey. It was awesome, full of aging hipsters like myself who made special plans to go out and shout along like they used to.

On the surface, That Dog sound like a relatively typical post-grunge alt-rock outfit, and their biggest hit "Never Say Never" is one of their least evolved—it's sonically fierce but reliant mostly on a big honking riff in the chorus. (Tellingly, the band sort of breezed over it during the set, partially because it comes pretty early in the tracklisting but also because it doesn't seem that interesting to play.) But they actually deploy quite a few bits of sonic weaponry, including a knack for off-kilter harmonizing and a willingness to flesh out their guitar/bass/drum arrangements with various strings (band co-founder Petra Haden, who is no longer a member of the group, is a classically-trained violinist). "Long Island" has a big hook in the chorus but also features a handful of harmonic dips and structural dives that would have confused modern rock radio programmers in 1997. But it's a smash from a parallel universe, particularly with lines like, "By definition a crush must hurt, and they do/ Just like the one I have on you." Sleater-Kinney's Dig Me Out also turned 20 on Saturday, and while it remains a more definitive historical hitching post in female-fronted rock, Retreat From the Sun shouts, frets, and shakes it off with just as much aplomb.

Over the course of their first three albums, Fall Out Boy followed a jaw-dropping arc: Their 2003 debut Take This To Your Grave was a mildly rugged bit of Warped Tour hardcore that got blown up to an IMAX version of itself on 2005's From Under the Cork Tree (that's the one with radio and MySpace staples "Sugar, We're Going Down" and "Dance Dance") and finally rode a rocket through the agit-pop ozone on 2007's Infinity on High. The band who made "Hum Hallelujah," the Leonard Cohen-winking album cut above, bears almost no resemblance to the one that banged out buzzy emo in Chicago basements. But that was always the plan, as the members of Fall Out Boy (and particularly bassist/lyricist/Internet penis icon Pete Wentz) were always thinking bigger. In fact, the band had already signed their major label deal when they put their first album out on Fueled By Ramen; Island allowed Take This To Your Grave to come out on an indie in order to bank some credibility, an age-old tactic that was also practice by fellow Chicago band Smashing Pumpkins a generation earlier.

Those stylistic and commercial leaps were calculated, but I find them no less laudable; in fact, if I had a band, that's exactly the journey I would want me group to follow with its opening triptych: a mildly unpolished debut followed by a reach for an arena-sized brass ring and finally settling on a blast of hybrid pop weirdness. There's nothing particularly revolutionary about Infinity on High (it's not like it's OK Computer or anything), but when it came out in 2007 it carried with it a bit of surreality that neither the emo devotees nor the top 40-listening newcomers knew how to process. It feels typical now (just about every band on Alt Nation sounds like their trying to ape the electronic punk mishmash of Infinity), but people were confused by its odd structures and chest-thumping swoop.

Fall Out Boy arrived a little too late to matter to me. By the time "Sugar, We're Going Down" got them onto the cover of Spin, I was already an adult with a job (at Spin). But songs like "Hum Hallelujah" do provide me with a bit of emotional tourism that simultaneously feels satisfying and kind of gross. Fall Out Boy were not a part of my youth, but they easily could have been. I didn't have much of an affinity for emo when I was growing up—I had processed Sunny Day Real Estate and had a compilation that had a Jawbreaker song on it, but I don't think I really processed the scene until much later (I'm still not sure I've ever listened to Rainer Maria). My hardcore friend Joe used to use "emo" as a derogatory descriptor for a song he found too pop leaning; this epithet was generally reserved for Rancid songs that ended up on the radio. But I was always a pop fetishist at heart, and I loved enough Green Day and Blink-182 tunes to know that had Fall Out Boy arrived in '98 I would have definitely been obsessed.

I still get a charge out of hearing the hook of "Hum Hallelujah," but it's a simulacra of a real, deeper feeling. (I recognize this as a problem with me, not with Wentz and the gang.) When Weezer's "El Scorcho" pops up on a playlist, I appreciate it both on an objective level (because it is a well-constructed bit of garage pop) and on a deeply personal one (because I am internally transported back to the thrill of discovering the song, diving into Pinkerton, and using the track as fuel to help me get over a girl). It's fundamental nostalgia, gently brushing against an old bit of my psyche and illuminating a mild throb in my memory. When I listen to "Hum Hallelujah," I get that same kind of satisfaction, but my brain has to make an active leap to get there. I am essentially projecting the song into my own past, and recognizing that if it had existed alongside some of the other songs that were actually there in real time, then it would have the same effect on me now. I'm essentially tricking myself into believing that "Hum Hallelujah" was a part of my youth even though it absolutely was not.

Why am I able to fool myself like this? Most likely because I recognize that a handful of Wentz's lyrics would be the sort of phrases I would have scribbled in the margins of my AP Government notes and possibly tried to pass off as my own turns of phrase. I guarantee that 16-year-old Kyle would think that "I thought I loved you/ It was just how you looked in the light" was a brutal burn, and he would have daydreamed about getting a tattoo with the line "One day we'll be nostalgic for disaster." (If you couldn't tell by any of this, 16-year-old Kyle was a complete asshole.) Ironically, the lyrics of "Hum Hallelujah" keep me from fully enjoying the song as an adult. In high school, I would have forgiven the line "A teenage vow in a parking lot/ Til tonight do us part," but now today it just feels clunky and leaden. "Hum Hallelujah" makes me feel it without feeling it, but I'll take a pristine fake if I don't have to think about it.

I have not been sleeping well. Or rather, let me rephrase that: I fall asleep and stay asleep and wake up (relatively) well-rested, But lately while I am asleep, I have been accosted by nightmares. They range in emotional spectrum from mildly eerie to alarmingly terrifying, but they all have an intensity that is undeniable and far more vivid than anything I have experienced in the past. Maybe it's my diet, or maybe this is all part of the aging process.

If there's any upside to this, it's that I now really understand the interior logic of the video for Nine Inch Nails' "Closer." Released as the second single from The Downward Spiral in 1994, "Closer" remains as unlikely a hit as there ever has been. "Closer" wasn't just a rock radio hit (it landed at number 11 on the Billboard Modern Rock chart) but also a bizarre pop crossover (it somehow climbed to number 41 on the Hot 100 and remains Trent Reznor's third highest-charting pop tune). That's a particularly impressive turn for a song whose chorus is "I want to fuck you like an animal."

Part of what made "Closer" a larger cultural moment was the music video, which was directed by Mark Romanek and was immediately placed into heavy rotation on MTV when it arrived in May of '94. The clip pulls from a handful of inspirations, particularly the decay-infused art of Joel-Peter Witkin and the creepy short films of the Brothers Quay. There's no real narrative—Reznor just sort of poses, sings, and hangs around a dusty storage facility for sideshow performers. Thanks to a healthy amount of nudity and one particular instance of implied animal torture, a lot of the "Closer" clip had to be edited down in order to meet MTV's strict broadcast requirements, and while a handful of images are simply blurred out, there are a handful of moments in the video wherein the footage is simply replaced by a placard that says "Scene Missing." It has a Nine Inch Nails logo on it, so it felt like a legitimate part of the video and not an artificial drop-in. Strangely, that legitimacy made the clip feel even eerier than it already was. My thought process was, "Considering how messed up some of the other images were in the video, what could possibly be disturbing enough to eject entirely?"

I showed up somewhat late to the "Closer" party, as I didn't see the clip until the end of 1994 as part of MTV's year-end countdown. It was relatively late at night and I was by myself, and the stillness of the evening and the darkness of the room made "Closer" feel like a broadcast from a parallel dimension—a dimension full of steampunk organs and roaches caked in sawdust. It unfolded like a nightmare—odd, upsetting, and yet still curiously intriguing. The "Scene Missing" placards were certainly part of it, and by the time I finally got around to seeing the unedited version of "Closer" (which is the only one you can find anymore) when I was in college, the whole thing seemed a little anti-climatic, and the stuff that was taken out seemed tame in comparison with the blankness my imagination had to fill. I should have known that kind of darkness can only come from within.

For me, Sleater-Kinney was one of those bands I read about for years before hearing any of the actual music. That was a general pitfall of music access when this album arrived in '97. My beloved Spin had declared Carrie Brownstein, Corin Tucker, and Janet Weiss an extremely good and important group largely based on their third full-length Dig Me Out. But though I was able to read quotes from the women and follow the arc of their career and do close readings of the criticism surrounding their music, I could not physically find a copy of Dig Me Out to save my life. Mail order was available but felt sketchy, and though CDNow was operational, this was still in the era before everybody felt comfortable buying most everything online.

This was not an unusual development for me during my high school days. There were a handful of oft-referenced bands about whom I knew many intimate details but could not whistle one of their songs. Pavement was a good example—since rock writers adored Pavement, they were often held up as a point of comparison or as a sideways reference. So though I knew about Stephen Malkmus' affinity for Boggle and was familiar with the lyric sheet from "Range Life," I don't think I actually heard a full-length Pavement album until 1999, and even then it was the limp finale Terror Twilight. (Freshman year of college, which brought with it my first high speed Internet connection and a Napster account, was when I finally heard Slanted and Enchanted in full.) This cycle dissipated roughly around the arrival of higher-quality streaming audio in 2001, as I recall the last band whose sound I had to construct for myself based on words written about them was the Strokes (and even then I failed miserably—I expected Is This It? to sound like Aerosmith's Rocks).

Such was the case with Sleater-Kinney, though I did manage to finally get around to hearing Dig Me Out even as they were becoming slightly bigger stars in the aftermath. At some point during the summer before my senior year, I was sent on an audition to do voices for a computer game called Rescue Heroes (it's a franchise that later became absolutely fucking gigantic). I got completely lost on my way to the studio (it was somewhere in western Connecticut, an area I knew little about). I have no idea what town I was in, but I do know that I passed by a record store that was going out of business. Assuming I was already late and may never arrive at the audition anyway, I popped in to get my bearings and to sample the wares. The selection had already been pretty thoroughly picked over, though the one place where the greatest cross-section of bargain and selection was in the racks of cassettes. Since my car still had a tape deck, I tended to make myself mixtapes for driving but did pick up the occasional album in the format, which I thought had been long dead but still survived (there were brand new albums on tape in the racks at this place). For two bucks a piece, I grabbed a copy of John Coltrane's A Love Supreme (still the only classic jazz album I've spent any time with), Deftones' Around the Fur (easily one of the five best albums from the nu-metal era), and Dig Me Out. I listened to the Sleater-Kinney first, as it had been the most built up for me and felt like the climax of a particularly grueling development period. It was well worth it, as everyone knows now that Dig Me Out is a pretty perfect collection of jittery garage punk drizzled with just enough caramelized pop sugar to make the rabble-rousing go down smooth. I love the stark savagery of "Buy Her Candy," the track that stood out to me most on that first listen. I was transfixed by Tucker's remarkable voice, which always sounds like it is on the verge of collapsing but is powered by a combination of nervous energy and the sheer will of necessity. The one bummer about "Buy Her Candy" is that it has no drums, which puts the bone-breaking Weiss on the sidelines. Otherwise, it was the perfect entry—one that proved elusive but ultimately made sweeter by the quest.

I subscribe to Apple Music. This song is not on Apple Music, though it is on Spotify, which I do not subscribe to but my wife does. Also, the only recording of Lanegan's version of this accidentally haunting Nick Lowe song comes from the soundtrack to the fucking Hangover Part II. Nothing in the future makes sense.

Three things stand out in this music video for a single from Canadian country-rockers Cowboy Junkies' seventh album Lay It Down.

First, it was filmed at the El Rey Theater on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, only a few blocks from where I currently live. While some of the base architecture remains in tact, the neighborhood surrounding the El Rey has changed a ton in the two decades since this was shot.

Second, it features Janeane Garofalo, who was probably a pretty huge get for Cowboy Junkies in '96. Garofalo (whose name I have never spelled correctly on the first try) was at the peak of her fame, having just come off a breakout performance in Reality Bites, a movie-stealing performance in Bye Bye Love, an extremely well-received HBO stand-up special, and a top-lining star turn in The Truth About Cats & Dogs. She's lovely and understated here.

Finally, what was up with Cowboy Junkies? They're one of those bands whose most notable contribution to culture is actually a cover—their version of the Velvet Underground's "Sweet Jane" got passed around a lot on soundtracks and mixtapes in the '90s (I had it on no fewer than four compilations). Their whole worldview seem to come from the idea that bluegrass is fine but it should be infinitely duller. They're a confusing act, and this was not a hit. But on the bright side: Garofalo!

When I was first becoming a music snob in my early teens, I was always doing one of two things: Convincing kids who only listened to the radio that indie groups were worth their time, and talking my fellow snobs into the idea that mainstream bands could be cool. One of the greatest examples of the latter carried me through the back half of the '90s in the form of a little band from Buffalo called the Goo Goo Dolls.

Though they had already made four albums by the time it arrived, "Name" was the drippy acoustic ballad that made the group with the silly name a radio and MTV staple in 1995. Though it was deeply uncool to like "Name" and its too-pretty singer, I still snagged a copy of A Boy Named Goo and was pleased to discover that the crossover single was an outlier on an otherwise solid collection of power pop tunes that fell somewhere between the shagginess of the group's garage-afflicted Replacements moves and the shiny pop product it would soon grow into. When Goo Goo Dolls were announced as the opening act for the Bush concert we were all going to see, most everybody in my show-going party rolled their eyes, but I got excited because I was looking forward to the band cranking through chunky bangers like "Naked," "Flat Top" and "So Long."

It became slightly less acceptable to embrace the Goo Goo Dolls by the time they signed a major label deal and released 1998's Dizzy Up The Girl. The basic tenets of the Goos sound were still in tact, but they were cranked up to 11. Instead of the understated ease of "Name," the big ballad on Dizzy was the bombastically cinematic "Iris," which had become a massive hit earlier in the year as part of the City of Angels soundtrack. They followed that single up with "Slide," a kinder gentler version of their hard jangle.

But there were still a handful of those punk-at-heart tunes on Dizzy Up The Girl, and my favorite remains "Amigone," a tune sung by Goos bassist Robbie Takac. His voice is snarlier than frontman Johnny Rzeznik's, and it lends the otherwise clean sheen of this four-chord jump just enough edge to reveal their gnarlier roots. I don't want to front on the rest of Dizzy, because "Black Balloon" and "Broadway" are both stellar constructions, but nothing reminds me that the Goo Goo Dolls secretly kick ass like Takac moaning, "Was the poison in our blood there all along?"

When I worked at Entertainment Weekly, we had a thing we did very briefly wherein we would go all-in on a new band, highlighting them in the magazine and producing some video content surrounding an interview and an in-office performance. I don't recall what we titled this thing, but I do recall that we only did it with two bands. The first was the Lone Bellow, an inoffensive folk pop trio that had a bit of a run during the ill-advised Mumfordmania from a few years ago. The other band was Feathers, a synth pop group from Texas that I was utterly obsessed with for about seven months.

Feathers' debut album If All Now Here was one of those records I got sent way in advance of its release—I think it arrived in May, but in my memory I was spinning it during the previous Christmas break. The band was primarily the brainchild of a woman named Anastasia Dimou, who was generally obsessed with dark '80s syhthpop and specifically fixated on Depeche Mode. If All Now Here is the best album Depeche never made, full of plastic noises that still sound visceral, a doomsday bass thump, and Dimou's airy alto rolling in and out of the melodic crevices like a fog. In fact, it recalls vintage Depeche so well that Dave Gahan drafted Feathers into being their opening act on a European tour (as well as a legendary SXSW gig).

If All Now Here never took off, though I still bust out "Believe" every once in a while. It will always stick with me because it was one of the songs Feathers played live in the office, and since you can't really do an unplugged version of what they do, they brought the entirety of their sound, which was loud and imposing and intense. I'm sure most of the office (and our neighbors) hated it, but I just couldn't get enough.

Skee-Lo will forever go down in history as a one-hit wonder, but his hit made a hell of an impact in the summer of 1995. Aided by a cheeky heavy-rotation video, "I Wish" was a breezy belt of hip-hop heaven delivered at the height of the East Coast/West Coast rap war. Though the gangsta paradise of Tupac and the Death Row crew was still relatively new, the pendulum had already swung a bit in the other direction, yielding the road to a brief period where summertime jams were the norm: Coolio's "Fantastic Voyage," Naughty By Nature's "Feel Me Flow," even Hammer's "Pumps and a Bump" provided a counterpoint to the dominant sounds of the era.

"I Wish" is a total jam, though Skee-Lo's series of requests have always struck me as off-kilter and often hilariously modest. Let's break them down.

I wish I was a little bit taller. This is a pretty lame request, though Skee does go above and beyond in the first verse. According to the Internet hive mind, Skee stood about five foot eight, and in my mind "a little bit taller" would translate to about six feet or so. That would be a huge increase for him, and certainly open up his opportunities on the basketball court. But then Skee demands that he were "six foot nine," which really elevates the scope of his hope. That's over a foot taller! While it certainly would put him in an elite streetball league, he would also undoubtedly have a hard time adjusting to his new elevation. His center of gravity would be all thrown off.

I wish I was a baller. If Skee means "baller" in the sense of "a guy who generally lives large," then that's a pretty decent request. But considering how much he fetishizes the ability to play hoops in this song, I think he just means, "I wish I had more talent within the confines of the triangle offense."

I wish I had a girl who looked good. Who wouldn't want this? But again, his goals are pretty modest—he doesn't want a model or anything, he just wants a non-ugly companion.

I wish I had a rabbit in a hat with a bat and six four Impala. There's a lot to unpack here. First, there's a whole contingent of people who contribute to terrible lyrics archive Genius who apparently believe that there's some sort of complicated slang running through this line, and that "a rabbit in a hat with a bat" is a reference to either a car or a loose woman. But considering how on-the-nose most of Skee's raps are, we can only assume that he want's an armed magician's pet. That's a super silly demand, but I sort of admire it. Meanwhile, the 1964 Chevrolet Impala is indeed a classic, but considering the '64 was still part of the Impala's problematic third generation, he'd probably have a lot less trouble with maintenance if he sought out a '66.

I wish I had my way. This is the key wish! It's a yearning for universal control over every aspect of your life. It's the only one that is buried in a verse (and the third one at that). However, Skee-Lo doesn't have a very ambitious set of goals for his sudden omnipotence—he merely declares that every day would be Friday, there are no more speed limits, and he would be allowed to name one of his children after Spike Lee's character in Do The Right Thing.

When I am by myself, I am most comfortable wearing headphones. Even when I'm home, where there are a multitude of listening options, I tend to want to throw on the cans and let them sit there. When I lived in New York, I put headphones on when I left work and did not take them off until I arrived by at my apartment, and I rarely ran an errand or went for a walk without them as well. Here in Los Angeles, I put them on when I park my car and don't take them off until I get into the studio.

It probably seems anti-social (and there's probably a part of it that is), but it's mostly about my own personal comfort. I've been like this for a long time—in fact, before I shared a bed with somebody, I would fall asleep wearing headphones most nights, dating back to when I was 12 or so. In the beginning, it was more about cramming in as much listening to my albums as I could over the course of a day; when I got a new CD, it was mostly about getting to know that piece of work from front to back. Later, in my post-college years, I would fall asleep at night listening to stand-up albums, which I guess I found comforting—after all, if I could hear someone else talking, how could I be alone?

I still spend most of my day wearing headphones, and now do a job that basically requires them. I no longer sleep with them, which I consider a victory, but back when I couldn't sleep without them, one of my go-to sleep albums was a compilation of Oasis b-sides that was one of my prized possessions circa '96 or so. In that era, there was a certain type of music store that dealt in bootlegs—typically live captures of concerts or homemade rarities compilations. Some came from (mostly foreign) indie labels, but looking back a lot of them seemed to be the results of a dude getting his hands on a CD burner.

There were a couple of stores that I could rely on for these types of releases, and I relished finding them. Some of my favorite recordings in history came from these not-quite-legal releases. I had a Pearl Jam live compilation that featured a lot of acoustic rarities, the entirety of Nine Inch Nails' Woodstock '94 performance, and a Foo Fighters live disc from their first world tour that also tacked on some of Dave Grohl's Pocketwatch demo and some in-progress versions of songs that ended up appearing on The Colour and the Shape (and a live cover of Angry Samoans' "Gas Chamber," which Grohl introduced as "one all you boys can bang around to," which remains a favorite phrase of mine). Some releases in the bootleg world took on a life of their own and are kinda-sorta considered canon in the discographies of some bands, like the Outcesticide series of Nirvana bootlegs that surfaced in the wake of Kurt Cobain's death. (Some research reveals that the Foos disc I had was called Fighting the "N" Factor and remains an oft-passed-around piece of ephemera for Grohl completists, particularly because it adds high-quality versions of some Nirvana SNL rehearsals.) These types of releases are pointless now, but in the time before Napster and iTunes and Spotify and YouTube, the only way to bring together rare tracks from your favorite bands was to either purchase a bunch of expensive CD singles or find a taper to trade with on a creepy message board or parking lot.

My favorite of these releases was a group of Oasis b-sides from the Definitely Maybe and (What's the Story) Morning Glory? era (and if my memory serves me correctly, there was also one recording from Oasis' entry of MTV Unplugged, which featured Noel on lead vocals). I really loved Morning Glory, and after hearing this group of tracks I came to a conclusion: Noel Gallagher must be the greatest songwriter in the world, because the songs he threw away were better than most anything else on the radio.

A bunch of these songs ended up getting released on the compilation The Masterplan in 1998, but I was pretty proud of the fact that by the time most of the world heard them, I was already intimate with their little details (the cough at the beginning of "Talk Tonight," the weird inconsistencies in the echo of "Rockin' Chair"). It always seemed like most of the tracks on The Masterplan were put there as-was, but I'm convinced that the version of "Underneath the Sky" I had was slightly different than the version that ended up officially released. I like that it sounds a little muddy while still shimmering, and the falsetto on the chorus often helped me drift off to sleep.

Snoop Dogg's discography is completely insane. Doggystyle is one of the most incredible debuts of all time, featuring a fully-formed MC rapping over some of Dr. Dre's most dynamic beats. (The fact that they were both at the peak of their powers in 1993 remains one of the more powerful minor miracles in music history.) Then he got embroiled in a legal battle, had a complicated extraction from Death Row Records, and eventually settled into a multi-faceted role of hip-hop ambassador that simultaneously involves a Woody Allen-esque schedule of releasing music and co-hosting a cooking show with Martha Stewart.

What's most impressive is that after the crossover success of Doggystyle (both "What's My Name?" and "Gin and Juice" were Hot 100 top 10s), Snoop essentially vanished from the pop mainstream for the better part of a decade (he re-emerged with the Pharrell-assisted one-two punch of "Beautiful" and "Drop It Like It's Hot"). During that in-between time, he was given a post-Death Row boost by Master P's No Limit Records, for whom he released a trio of albums at the turn of the century. They're all of reasonable-enough quality, though the best one is the middle entry, 1999's No Limit Top Dogg.

At the time, No Limit was a huge commercial and critical force in rap music. Lead star and central impresario Master P graduated from selling burned CDs out of his trunk to moving nearly a half million first week copies of the double album MP Da Last Don. At the time, Snoop's fluid, refined style seemed like it would not blend well with the minimalist trunk-thumping undercarriage provided by P's Beats by the Pound crew. It didn't always work, but No Limit Top Dogg has two things going for him. First, there are a handful of outside producers that contribute (including a returning Dr. Dre and old West Coast cohort DJ Quik), which makes it feel like a more dynamic record. The other thing that works remarkably well is that just about all the other rappers on the album (and there are a ton of guest spots) are operating at their peak and have finally figured out how to gel with Snoop's style. There's no greater example of that than on "Ghetto Symphony," which transposes the same sample of Otis Redding's "Hard to Handle" that Marley Marl used on "The Symphony" back in 1988. (Remarkably, that same sample has been used a bunch of times by a number of different hip-hop acts, including the Diplomats, 2 Live Crew, Everlast, GZA and Big Daddy Kane.) Everybody is on point here, particularly a not-yet-famous Mystikal (he was a little over a year away from "Shake Ya Ass") and a remarkably sharp Mia X (who on balance was probably the best pure rapper in the No Limit crew). It's a banger of a posse cut, and it lets Snoop be both playfully nimble and a tough roughneck simultaneously. It's the best version of Snoop, and my favorite.

In 2002, Spin published an article called "Not Bad For a White Girl" that was about the then-current quest within the music industry to discover and promote a white female rapper. Eminem was in the midst of his initial rise, buoyed not only by multi-platinum sales but also plenty of Grammy love (he was just coming off losing Album of the Year to Steely Dan). Marshall Mathers' rare combination of raw skill and head-turning novelty was too much to pass up, and the Spin story tracks a bunch of producers, executives, managers and wannabes trying to find (as one subject indelicately puts it) "the Britney of rap."

As the story points out, not only has the hip-hop world been hostile to white women, but it has in general been twitchy about women at all. Back in '02, the most notable female MCs at the time were Lauryn Hill, Missy Elliott and Eve, all of whom had scored the rare combination of commercial success and critical respect (though ironically none of those women has recorded very much since then). Lil Kim and Foxy Brown were already on the downswing of their brief pop window, and Salt-N-Pepa and Da Brat were already considered nostalgia acts even though neither was all that far removed from their commercial peak. Fifteen years later, the landscape doesn't look all that different. Nicki Minaj has certainly carved out a place for herself, but she has made plenty of moves that seem like she's not that interested in rap (and is currently being dunked on by a just-out-jail Remy Ma). After Minaj, who is the second-biggest MC with two Y chromosomes? Is it MIA, who only sort of raps and works very much outside the hip-hop universe? Is it Twitter novelty act Azealia Banks? By attrition, it might actually by Iggy Azalea, a woman I've always found talented but seems destined to be relegated to one-hit wonder status. There are plenty of extremely talented women working the mixtape circuit like Rapsody and Angel Haze, but the mainstream remains relatively bereft of the fairer sex.

The Spin piece highlights a handful of potential Feminems, but pretty much all of them outside of the already-established Princess Superstar became nothing at all. One of the rare exceptions is Invincible, a Detroit-based rhymer who was spoken about glowingly in the article but ironically declined to be interviewed for it. She still raps and functions as a local activist in Motown, and her 2008 album Shapeshifters is a pretty dope slathering of beats and rhymes. I'm a fan of the slightly jazzy aural assault "No Compromises."